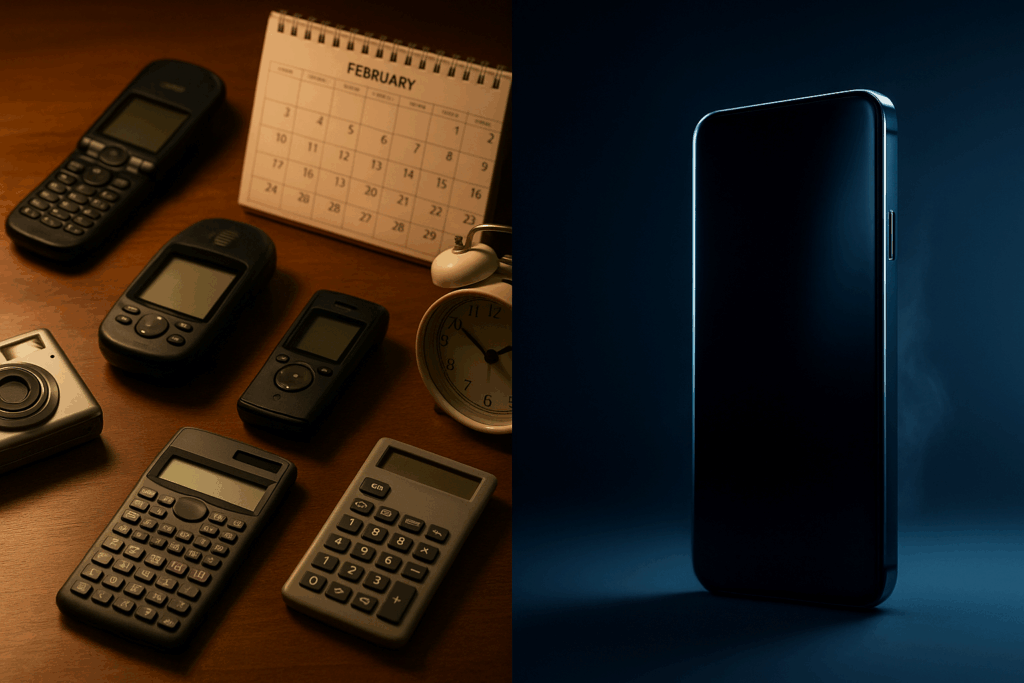

For the past 15 years, the smartphone has been the undisputed hub of our digital lives. With a touch-screen slab always in our pocket, we stopped carrying a dozen other gadgets – our phones became our cameras, our calculators, our calendars, our alarm clocks, our GPS navigators, even our flashlights. This convergence era saw the mobile phone swallow virtually every single-purpose device in its path, evolving into the dominant personal computing interface of the 2010s. But lately, there are signs that this once-unstoppable trend is finally hitting a plateau.

Smartphone innovation has begun to feel incremental. Today’s new phones aren’t jaw-dropping leaps so much as iterative tweaks – a slightly better camera here, a slicker design there. Global sales data bears this out: in 2023, smartphone shipments fell to just 1.17 billion units, the lowest level in a decade. After explosive growth in the 2010s, the market has flattened and even contracted in recent years. The basic reason is simple saturation – well over 4 billion people already have a smartphone, out of about 5.7 billion adults on Earth. In other words, nearly everyone who can afford a phone has one, leaving few new customers to acquire. Meanwhile, those of us with smartphones are upgrading less frequently. The average replacement cycle has stretched to around 40 months (over three years) as devices last longer and prices climb. Many consumers see little reason to buy a new phone every year or two now – last year’s model is usually “good enough.” In fact, a growing share of people are opting for refurbished phones rather than brand-new ones to save money and reduce waste.

All of this points to a maturing market. The S-curve is flattening out, as analyst Benedict Evans famously observed: “All the obvious stuff has been built… the new iPhone isn’t very exciting, because it can’t be”. We’re at the tail end of the smartphone’s reign as the primary focus of tech innovation. Smartphone shipments did tick up slightly in 2024 after two down years (IDC recorded a 6.4% rebound to about 1.24 billion units), but that modest growth was driven in part by economic recovery and aggressive promotions, not a new revolution. The overall trend remains one of stagnation. Industry analysts at IDC plainly state that while the smartphone “will remain the quintessential device for most,” longer replacement cycles and market saturation are “dampening new shipment growth”. Even the device makers seem to recognize this reality – for example, Apple (which rode the iPhone to become the world’s most valuable company) has been diversifying its offerings, from wearables to services, as iPhone sales level off.

Into this landscape of slowing smartphones comes a bold new signal of change: in May 2025, OpenAI – the AI research company best known for ChatGPT – announced it is acquiring a small hardware design firm called “io” in an all-stock deal valued at $6.5 billion. That alone turned heads, but the real surprise was who leads this little startup: Jony Ive, the legendary designer who helped create the iPhone itself. Ive’s company, with a team of around 55 ex-Apple engineers and designers, had been quietly working on “AI-native” hardware since its founding in 2023. OpenAI already owned a minority stake and had been collaborating with Ive’s team; now they’re bringing them fully in-house to spearhead a new hardware division. Ive will not formally join OpenAI as an employee (his independent design firm LoveFrom stays separate), but he’s taking on deep creative leadership across OpenAI’s hardware projects. In the words of OpenAI’s CEO Sam Altman, “no one can do this like Jony and his team”.

Why would a cutting-edge AI lab want to buy a boutique device maker? Because this partnership is a bet that the next era of personal computing will not be confined to the glass rectangles in our palms. It’s a bet on a post-smartphone future – one where AI-driven devices all around us form the new center of gravity. Altman has been open about his belief that new form-factors are needed to move beyond the screen. Ive, for his part, has hinted that our current gadgets feel dated: “The products we’re using to connect us to unimaginable technology, they’re decades old. Surely there’s something beyond these legacy products,” he mused in a video shared by OpenAI. In acquiring Ive’s “io” startup, OpenAI signaled that it intends to build that something beyond – the hardware that will define an AI-first computing paradigm. The deal (OpenAI’s largest to date) is set to close by summer 2025, and the company says the first fruits of this collaboration will be shown in 2026.

This development has electrified conversations about what many are calling the “post-smartphone era.” Just as the iPhone’s launch in 2007 marked the beginning of the mobile convergence age, OpenAI and Ive’s alliance in 2025 may mark the beginning of a new age of AI-native devices. In this feature, we’ll explore how smartphones came to absorb nearly every gadget in our lives, why that convergence wave is cresting, and what might come next. We’ll map out emerging categories of AI-centric hardware – from wearable assistants to ambient smart environments – using the data and trends already in motion. We’ll also consider how the tech giants (Apple, Google, and others) are positioning themselves for this shift, the regulatory and design challenges it raises, and lessons from past transitions in computing. Finally, we’ll take a speculative peek at how personal computing might look by 2030 if AI-driven devices truly take center stage.

Table of Contents

ToggleThe Smartphone’s Convergence Triumph – and Slowdown

It’s hard to overstate how thoroughly the smartphone subsumed other devices over the last decade and a half. Consider a snapshot from the mid-2000s: you might have owned a point-and-shoot camera for photos, a GPS unit for your car, an MP3 player for music, an alarm clock on your bedside, maybe a handheld game console, a Flip camcorder, a voice recorder for notes, plus stacks of maps, books, magazines, and CDs. Today, all of those functions (and then some) live inside the slim rectangle of glass in your pocket. As one retrospective quipped, “from cameras to calendars, and many more in between, the mobile phone has replaced countless things in your life”. The smartphone became the Swiss Army knife of personal tech. App developers and hardware makers raced to add ever more capabilities: turn-by-turn navigation, HD video capture, mobile banking, social networking, streaming TV – if you could imagine it, there was an app or feature for it. By the late 2010s, the smartphone wasn’t just a computing platform; it was the dominant computing platform for billions of people around the world.

This convergence yielded tremendous convenience and fueled a boom in industry growth. Between 2007 and 2016, annual smartphone shipments skyrocketed, reaching a peak of roughly 1.5 billion units a year (by some estimates) at the height of the boom. Smartphones became the fastest-adopted consumer technology in history – achieving mass-market penetration quicker than even the PC or the television. In the United States, for example, smartphone ownership climbed from near zero in 2007 to over 80% of adults by the late 2010s. Globally, smartphone user numbers passed 3 billion, then 4 billion, on their way toward the natural limit of the adult population. The speed of this adoption was unprecedented (one analysis noted that smartphones matched the household penetration of TVs in a fraction of the time). And as their reach grew, smartphones devoured the markets of those older devices – digital camera sales fell off a cliff, standalone GPS navigation units practically vanished, and so on. The convergence was so complete that many younger users today have never owned a separate camera or music player; the phone has always been the all-in-one.

However, as noted, the era of breakneck growth through convergence is plateauing. The very success of smartphones in conquering the electronics ecosystem means there’s not much left for them to absorb. By 2020, the average consumer’s daily digital needs – communication, web access, media, navigation, etc. – were largely met by their phone and a few other devices (like perhaps a laptop for work). Yearly upgrades started to feel less necessary when the differences became minor. A mid-range phone from a few years ago could run all the same apps the newest flagship could. As a result, global smartphone shipments began a multi-year stagnation and decline. IDC data shows 2017–2019 shipments stagnated and then the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 disrupted sales further. A brief rebound in 2021 gave way to steeper declines in 2022 and 2023, as inflation and market saturation caused consumers to pull back. The 1.17 billion units shipped in 2023 was down 3.2% from the prior year and marked the lowest annual total in 10 years. In mature markets like the U.S. and Europe, virtually everyone who wants a smartphone already has one, and many are perfectly satisfied holding onto their devices longer. Analysts note that improved durability and higher prices have “lengthened the replacement cycle” to the point that 40-month ownership is now average. The effect on new sales is stark – a phone that might have been replaced after 2 years is now stretched to 3 or 4 years of use.

Not only are units flat or declining, but consumer excitement has waned. Ask smartphone users what new feature they’d really love that their current device lacks, and you might get a lot of blank stares. Foldable phones with flexible screens made a splash in 2019, offering a novel take on the form-factor, but to date foldables remain a niche segment (around 25 million foldables may ship in 2025, a fraction of the market). The vast majority of phones are still the familiar rectangle. There’s a sense that we are reaching the end of what the slab smartphone can meaningfully do – or at least, the end of how much better it can get at doing those things. This doesn’t mean smartphones are going away (far from it – IDC projects a return to modest growth in 2024 and beyond, and “quintessential device for most” status for years to come). But it does suggest we’re ripe for the next paradigm – a shift in focus to new kinds of devices that could supplement, or even eventually succeed, the smartphone as the center of personal tech.

Betting on What Comes Next: OpenAI + Ive and the Post-Smartphone Play

When news broke that OpenAI was buying Jony Ive’s hardware startup, it sent a clear message: one of the world’s leading AI companies is serious about building physical devices, and they’ve enlisted the world’s most celebrated gadget designer to do it. The combination is striking. OpenAI is synonymous with advanced software (its GPT-4 language model and ChatGPT assistant have become household names), yet until now it has never sold a consumer device or really any hardware. Jony Ive, conversely, is synonymous with iconic hardware – his design imprint is on the iMac, the iPod, the iPhone, and more – but he has never worked in the realm of AI software. By acquiring Ive’s firm io, OpenAI is effectively marrying cutting-edge AI brains with top-tier industrial and product design. It’s a signal that whatever device they create will be AI-native: conceived from the ground up around artificial intelligence capabilities, rather than adding AI as an app or afterthought to an existing gadget.

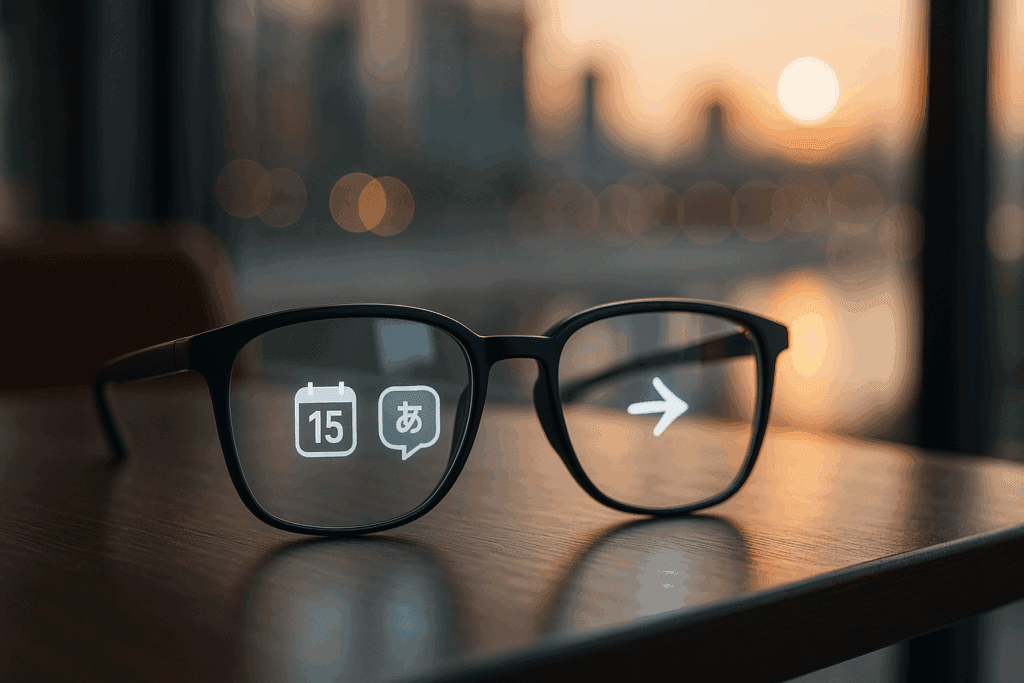

What might an “AI-native” device look like? Both OpenAI and Ive have been tight-lipped on specifics (unsurprisingly – the first product isn’t due until 2026). However, clues have surfaced. Rumors over the past year suggested Altman and Ive were exploring designs for a new consumer device aimed at “moving beyond the smartphone’s reliance on screens”. Reporting from The Information and others hinted at devices that might leverage voice interaction, cameras, and ambient sensors to integrate AI seamlessly into daily life – perhaps something wearable or a novel home device. Ive himself, in a short clip released by OpenAI, criticized that current products are “decades old” in their UX paradigm and implied a need to reinvent how we interact given the advent of powerful AI. This has led many observers to speculate that the OpenAI-Ive device could be a screenless personal assistant of some sort – maybe a smart wearable that you talk to and hear from, rather than a phone you look at and touch.

In fact, we already have a rough proof of concept for such a gadget: the Humane AI Pin, a much-buzzed-about wearable that launched in late 2023. Humane – a startup founded by former Apple employees – debuted the AI Pin as a tiny clip-on device with no traditional screen, designed to be an AI-driven concierge that you control via voice, gestures, and a projector. The Pin essentially functions as a ChatGPT-on-your-collar, connecting to OpenAI’s GPT-4 for brains. Early reviewers noted it “does a lot of smartphone things – but looks nothing like a smartphone”. It can answer questions, transcribe notes, translate languages, and even project information onto surfaces, all without a handheld display. The concept is exactly in line with “AI-native hardware” – a device built entirely around AI interactions (talking and listening to a large language model) instead of around apps and touchscreens.

The Humane AI Pin’s initial reception, it must be said, has been mixed. For $699 (plus a subscription), reviewers found it limited and sometimes confusing, with The Verge bluntly stating that it’s “not yet entirely clear what you’re supposed to use it for”. The first-generation Pin might not be the hit that replaces anyone’s iPhone just yet. But it is a trailblazer – a real consumer product showing what a post-smartphone device could be. Notably, OpenAI was involved in the Pin (Humane’s software routes queries to OpenAI’s models, and OpenAI has partnerships in that ecosystem). One might say OpenAI got a front-row look at this experiment – and perhaps learned some lessons. Now, with Ive’s design genius on board, OpenAI may aim to take the core idea (a wearable, ambient AI assistant) and execute it better. Altman certainly has grand ambitions; when announcing the Ive deal, he posted that he’s “excited to try to create a new generation of AI-powered computers”. The wording “AI-powered computers” hints that this is about defining a new platform, not just a one-off gadget.

Crucially, OpenAI’s move fits into a broader picture: across the industry, efforts are underway to imagine life after the smartphone. Let’s look at the leading contenders for what form this new paradigm might take. Three broad categories of AI-native hardware have emerged (often overlapping with one another): wearables, spatial computing devices, and ambient AI tools in our environments. Each category is backed by real products, prototypes, or market trends here in 2025, and each is likely to play a role in a post-smartphone computing landscape.

Mapping the New AI-Native Hardware Landscape

1. Wearables as Personal AI Companions: Smartphones might be plateauing, but wearable devices have been on a steady rise. In 2024, over 534 million wearables were shipped worldwide – a category that spans smartwatches, fitness bands, wireless earbuds, AR glasses, and even smart rings. These on-body gadgets are increasingly sophisticated and, importantly, many are starting to incorporate AI features. Take the Apple Watch, for example. It began as a phone accessory, but recent models have machine learning chips that can do things like analyze health patterns or transcribe speech on-device. Or consider earbuds like Apple’s AirPods and Google’s Pixel Buds – they now offer real-time language translation and voice assistant access. With generative AI, one can imagine earbuds becoming conversational agents in your ear, whispering answers to questions or providing guidance on the fly. Indeed, tech firms are exploring this: there are concept demos of AI assistants that live in your earbuds, ready to contextualize what you’re hearing or help you communicate in another language.

The Humane AI Pin mentioned above also falls into the wearables camp. It’s worn on the body (clipped to a shirt) and meant to be a constant companion. Its lack of screen is made up for by voice interaction and a mini projector that can display a contextual UI when needed (for instance, projecting an incoming call’s caller ID onto your hand). Similarly, there are rumors of other wearable AI pendants or badges in development. The appeal is to have an assistant that is “always on, always with you,” but less intrusive than a phone. You wouldn’t be hunched over a screen; instead you’d speak naturally and get spoken or subtle visual feedback. Privacy and social acceptance are challenges here – a device that is always listening (even if it has a noticeable “trust light” like the AI Pin does) can make people uneasy. And interacting by voice in public can be awkward. Designers are exploring solutions, such as wake-word activated listening (to avoid constant recording) and making the form factor discreet or fashionable (so it feels like wearing an accessory, not a chunk of tech). The bottom line: Wearables are poised to carry forward many tasks we use phones for, but in a more background, context-aware way. Even traditional wearables like watches could benefit – imagine a future Apple Watch with a truly smart AI assistant that can proactively coach you through your day without needing to pull out a phone at all.

2. Spatial Computing and Mixed-Reality Devices: Another major category is what some call spatial computing – devices that blend digital content with the physical world, typically through advanced displays like AR (augmented reality) or VR (virtual reality) headsets. Companies have been chasing AR and VR for years, but 2023–2025 has seen a new surge of momentum, especially with Apple’s entry into the fray. Apple unveiled the Vision Pro headset in 2023, a high-end mixed reality device that it explicitly pitched as the start of a new computing platform (“spatial computing”). While the first-generation Vision Pro is expensive ($3,499) and aimed initially at early adopters and developers, it demonstrates what the future could hold: wearing a computer on your face that can overlay 3D digital objects onto your view of the real world. Apple’s system allows apps to float as if in mid-air around you, controlled by eye gaze, hand gestures, and voice – no keyboard, no phone needed.

AI plays a crucial role here as well. For AR/VR to be compelling, it needs to understand the user’s environment and intentions, which is a task for multimodal AI (AI that can process visual, audio, and other inputs together). In fact, IDC notes that the latest wave of headsets is coming with “glasses with displays and multi-modal artificial intelligence” built-in. Think of an AR headset that not only shows you information, but can see what you see and hear what you hear – and an AI can provide context. For example, you look at a product and ask, “What is this?” and the device’s AI vision can identify it for you. Or you’re traveling in a foreign country and all the signs you see are instantly translated in your view. These are not far-future fantasies; primitive versions exist today (Google’s smartphone app can translate signs via camera, and AI vision models like OpenAI’s GPT-4 can describe images). In headset form, it could happen seamlessly in real-time.

The AR/VR market today is small but growing. Roughly 9–10 million AR/VR headsets shipped in 2024, and forecasts predict a significant ramp-up by the late 2020s as devices get smaller, cheaper, and more capable. Meta (Facebook’s parent) remains the market leader, having sold millions of its Quest VR headsets for gaming and social experiences. Meta’s long-term vision is true AR glasses and it has poured tens of billions into that effort. Google, after an early foray with Google Glass a decade ago, is also back in the mix – it has reportedly been developing an Android-based XR (extended reality) platform and partnered with Qualcomm and Samsung to build next-gen glasses. Microsoft has its HoloLens (focused on enterprise AR) and no doubt is eyeing consumer scenarios too (especially given Microsoft’s huge investment in OpenAI – one could imagine a future “Windows for AR” or something along those lines).

Critically, Apple, Google, Meta, and others see spatial computing as a chance to define the next platform and not be left behind. If AR glasses eventually replace some of our screen time on phones, the company controlling the leading glasses OS and app ecosystem will be immensely powerful – much as Apple and Google dominated in mobile. That’s why IDC expects “platform rivalries” in XR to heat up among these players. For the consumer, the promise of spatial devices is a more immersive, natural way to use technology: rather than staring down at a phone, you’re looking up and around, with digital info integrated into your world. It’s like bringing the internet off the screen and into real life. But again, there are hurdles: current headsets are still bulky, people may not want to wear them for long periods, and there are privacy concerns (wearable cameras can feel invasive to bystanders – a lesson from the Google Glass backlash). Still, by 2030 we might have glasses indistinguishable from normal eyewear that can do what our smartphones do and more. OpenAI and Ive’s team are likely considering this arena too – perhaps not to build a full AR headset (that’s a massive undertaking) but to ensure whatever they create fits into a future where spatial computing is mainstream.

3. Ambient AI in the Home and Car: The third category is ambient computing – spreading intelligence into the spaces around us. Instead of a personal device that you carry or wear, think of AI living in your home environment, your workplace, your car, embedded in everyday objects. We’ve already seen a precursor to this with the rise of smart speakers and voice assistants over the past 8 years. Devices like the Amazon Echo, Google Nest Hub, and Apple’s HomePod brought always-listening voice helpers (Alexa, Google Assistant, Siri) into millions of homes. As of mid-2020s, smart speakers are in roughly a quarter to a third of U.S. households and a significant number of homes in Europe and Asia too. However, these first-gen assistants have been fairly limited – great for setting timers or playing music, decent at answering factual questions, but not truly “smart” in a conversational, task-performing sense.

Now, generative AI is supercharging these assistants. In late 2023, Amazon announced a major upgrade to Alexa, powered by a custom large language model, to make Alexa more conversational and capable of complex requests. Google is likewise working to integrate its advanced AI (the kind behind Google’s Bard chatbot) into the Google Assistant. The idea is that instead of stilted, pre-programmed responses, your home assistant could hold natural conversations: you might say, “Alexa, help me plan dinner tonight – I have chicken and bell peppers,” and get a thoughtful answer with recipe suggestions, maybe even automatically adjusting a smart oven’s temperature when it’s time to cook. Ambient AI means the intelligence is all around, not just in one device. We’ll see more appliances and fixtures imbued with sensors and AI – from smart thermostats that anticipate your comfort needs to security systems that can distinguish between an intruder and the family cat. The CHIPS Act and similar initiatives, which invest in semiconductor capabilities, recognize that as everyday objects get smarter, we’ll need a lot more specialized chips (and we’d like to produce them domestically for both economic and security reasons). So there’s governmental support to push AI into the “Internet of Things,” making ambient computing a big focus area.

One particularly exciting (or depending on your view, unsettling) extension of ambient AI is in our vehicles. Modern cars are already packed with chips and software, and now they are becoming platforms for AI assistants. General Motors, for instance, has been exploring the integration of ChatGPT into future cars. Imagine a virtual co-pilot in your car’s dashboard that you can talk to as freely as you’d talk to a human passenger. You might ask it to adjust the car’s settings, explain a warning light, or even help you negotiate a lease by crunching numbers with you on the fly. A GM executive described this not as just voice commands 2.0, but as a promise that “customers can expect their future vehicles to be far more capable and fresh overall” thanks to AI. Other automakers are doing similar: Mercedes-Benz launched a beta where its in-car voice assistant was augmented with ChatGPT’s abilities, allowing for more conversational interactions. Tech companies see cars as the next battleground – Microsoft, for example, is partnering with automakers (including investing in GM’s self-driving division) to embed its tech in cars. The car of 2030 might effectively be a rolling AI computer, with the windshield as a display, your voice as the interface, and an AI system coordinating navigation, entertainment, and vehicle functions in the background.

In short, ambient and environmental AI is about dissolving the technology into the background of daily life. Instead of carrying a single do-it-all device (smartphone) everywhere, we’ll be surrounded by many devices and sensors, each perhaps specialized (your watch monitors health, your glasses handle visual info, your car handles mobility, your home listens and responds to needs) but all connected through AI. This is sometimes called an “ubiquitous computing” vision – computing everywhere, but nowhere in particular. It’s a very different mindset from the iPhone era’s “one device to rule them all.” The OpenAI-Jony Ive project likely aligns with this philosophy: rather than building another rectangle for our pocket, they’re likely aiming for something that complements or ties together these ambient experiences. It might be a wearable or home device that serves as the intelligent orchestrator for all your other gadgets, powered by OpenAI’s algorithms but presented with Ive’s trademark user-friendly design.

Big Tech, Big Questions: Platforms, Policy, and Design in a Post-Phone World

A shift of this magnitude – from the smartphone-centric world to an AI-centric, multi-device world – carries huge implications for the tech industry and society. First, consider the big tech platforms that have dominated the smartphone era: Apple, Google, Samsung, and to a lesser extent Microsoft (via its investment in mobile software and now OpenAI) and Amazon (with its Android-based tablets and Alexa devices). These companies have established empires around smartphones. Apple built an ecosystem of iOS apps and services generating tens of billions in revenue. Google’s Android powers the majority of phones worldwide, feeding Google’s search and ad business with mobile eyeballs. If people start to use traditional smartphones less in favor of new devices, these firms will need to adapt aggressively – or risk losing their grip on our attention and wallets.

Apple’s strategy seems to be “if something will replace the iPhone, we’ll be the ones to build it.” The company has been methodically expanding into wearables (Apple Watch, AirPods) and now spatial computing (Vision Pro). Notably, Apple’s wearables business is already huge – its revenue from Watch and AirPods combined rivals Fortune 100 companies – and these products keep users tied into the Apple ecosystem without always needing an iPhone in hand. With the Vision Pro headset and its planned successors, Apple is trying to define the next interface (fully intending, it appears, for Vision to eventually do many things a phone does). Tim Cook’s Apple is investing heavily here, arguably to ensure that if an AR glasses revolution comes, Apple won’t miss out the way Microsoft missed the smartphone revolution. The OpenAI + Ive news was even seen by some analysts as a “shot across the bow” for Apple – a warning that nimble outsiders are also gunning for the post-smartphone throne. Apple’s CEO was dubbed a “peacetime CEO” in one commentary, implying that Apple, atop the smartphone hill, might be complacent while a battle for the next hill is beginning.

Google finds itself in a more precarious spot. While it dominates smartphone operating systems with Android, Google’s attempts at building hardware beyond phones have been hit-or-miss. It leads in some ambient computing areas (Google Assistant is arguably the most advanced voice AI until very recently, and Google’s Nest smart home products are popular). But Google famously flubbed early AR glasses (Google Glass), and it doesn’t have a strong wearables lineup aside from the Fitbit acquisition and Pixel Watch (which are far behind Apple Watch in market share). For Google, the rise of AI-native devices is both an opportunity and a threat. The opportunity is that Google’s core strength – information and AI – could shine in a world of ubiquitous assistants. Google has world-class AI research (it pioneered the “Transformer” technology that underpins GPT models) and could deploy that across all sorts of devices. The threat is disintermediation: if a new interface doesn’t rely on traditional web search or app paradigms, Google’s advertising cash cow could be bypassed. For instance, if people in 2030 get their questions answered by a personalized AI assistant device (that maybe pulls info from a variety of sources), they might not be typing queries into Google.com and clicking ads at nearly the same rate. No wonder Google is racing to integrate Bard AI into search and products – they need to stay at the center of user queries in whatever form those queries happen.

Amazon and Meta also have stakes in this game. Amazon has Alexa and a massive presence in the home. It will want Alexa (and by extension Amazon’s services) to be the intelligence in others’ ambient devices, not just its own Echo speakers. Amazon already tried some out-of-the-box hardware ideas (like Echo Frames glasses and a short-lived Alexa smart ring), showing they’re experimenting beyond speakers. Meta (Facebook) sees AR/VR as existential – CEO Mark Zuckerberg has been vocal that whoever controls the next computing platform will not have to depend on rivals (as Meta currently depends on Apple’s iPhone and Google’s Android to get its apps to users). That’s partly why Meta is all-in on the metaverse vision and devices like Quest. If people start socializing and working in AR/VR spaces that Meta controls, that could reduce reliance on smartphones as well.

Then there are the new entrants like OpenAI (backed heavily by Microsoft’s capital). OpenAI doesn’t have a legacy phone business to protect, so it can be disruptive. Its value lies in its AI models and ecosystem. By moving into hardware, OpenAI could try to set the standard for how AI is experienced by consumers – essentially aiming to be the “Intel Inside” or the Android of the AI device era, except with more direct control. But established giants won’t just roll over; we might see partnerships (for instance, OpenAI’s tech inside Microsoft or other partners’ devices) or even competitive tension (imagine Apple developing its own rival AI models to avoid using OpenAI’s, so that it can offer a fully Apple-owned AI experience on future devices).

All this raises the issue of regulation and competition policy. Regulators like the U.S. FTC and the EU’s competition commission have grown wary of Big Tech extending monopolies into new domains. Any major moves – say, if Google tried to buy a leading AR hardware startup, or if Apple locked down an AR app store – would likely face scrutiny. In the case of OpenAI’s purchase of Ive’s company, the deal is significant ($6.5B) but since OpenAI is not (yet) a dominant player in consumer hardware, it’s not an antitrust concern in the traditional sense. However, regulators will be watching how the AI and device markets converge. One concern is user data and privacy: a world of ambient AI means a lot more data being collected (audio, video, sensor data from homes and wearables). Regulators may push for stronger privacy safeguards, transparency, and even limits on how and where these always-on sensors operate. Europe’s GDPR and upcoming AI Act, for instance, will require that AI systems be explainable and that sensitive personal data isn’t mishandled – those will apply to something like an AI wearable that records environment data. There’s also talk about merger scrutiny in the AI space; governments don’t want a few companies buying up every AI startup and consolidating power unchecked (the way, arguably, Facebook bought Instagram/WhatsApp or Google bought numerous startups in the 2010s). OpenAI’s independence is somewhat protected by its cap-profit structure and ties with Microsoft, but if it starts to become the ecosystem for AI hardware, that will attract attention.

Finally, from a product design and societal perspective, the post-smartphone era raises new challenges. Privacy is a big one: smartphones are personal and discrete – they can take photos and videos, but generally only when we choose. What happens when our glasses have cameras running or our home has mics in every room? Ensuring these devices have robust privacy (like hardware kill-switches for sensors, clear indicator lights when recording, local processing of data whenever possible to minimize cloud exposure, etc.) will be key to user trust. Jony Ive’s team is likely already thinking about this – how to design an AI device that people want to use intimately without feeling spied on. There’s also the interaction design question: we’ll need new UI paradigms beyond touchscreens. Voice and conversation are one modality, but voice alone isn’t always ideal (public use, noise, etc.). Gesture controls, gaze controls, even AI that anticipates needs could play a role. For example, an AI might learn your habits so well that it takes action without you explicitly asking (like dimming the lights and turning on calming music when it senses you’re stressed in the evening). That kind of proactive AI flips the interaction model – it requires design for consent and control (you don’t want your devices doing unwanted things “for you” without easy override).

Another design trend is multimodality – devices will use many sensors and outputs in tandem. A future device might simultaneously track your eye movement, listen to your voice and background sounds, monitor your heart rate (via a wearable) and cross-reference all that to understand context. For instance, if your wearable detects an elevated heart rate and your smart home hears a loud bang, it might deduce you’ve had a sudden fright or accident and automatically ask if you need help. This is powerful but also borders on invasive if not handled carefully. Designing AI products that feel helpful, not creepy will be a fine line. Companies will likely emphasize privacy features (such as on-device AI processing for certain tasks, end-to-end encryption for communications between your devices, and giving users clear opt-ins for data sharing).

We should also recall earlier tech transitions for clues on what to expect. One pattern: the incumbent leaders of the old paradigm often struggle with the new. IBM thrived in mainframes but missed the early personal computer market until it partnered with Microsoft. Microsoft dominated PCs but completely missed the smartphone revolution (Windows Phone never stood a chance against iOS/Android). BlackBerry and Nokia were kings of pre-iPhone mobile but failed to adapt to the touchscreen app-centric model that Apple and Google ushered in. Now, Apple and Google themselves face that test: can they pivot from smartphone dominance to whatever comes next? They have advantages (vast resources, strong ecosystems) but also the innovators’ dilemma (they can be risk-averse to change that might undermine their current cash cows). This opens opportunities for newcomers – perhaps OpenAI, or Humane, or some yet-unknown startup – to leapfrog with a fresh approach.

History also suggests that transitions are gradual and overlapping, not a sudden flip. PCs didn’t kill mainframes overnight; smartphones didn’t make PCs disappear (PCs are still around, just not the center of consumer tech). Likewise, even if AI devices rise, smartphones will likely stick around in some form for many years. The post-smartphone era might initially look like an expansion of our device roster rather than a replacement: we might carry a smartphone and wear an AR glass and have smart assistants in our home and car. Over time, as the new devices get better, one of them might subsume the phone’s role – perhaps the glasses or the wearable does enough that the phone becomes secondary. By the 2030s, it’s plausible the phone could fade into the background much as the desktop PC did for many consumers. But that will depend on how compelling and convenient the new experiences are.

Imagine 2030: A Day in the Life of the Post-Smartphone Personal Computer

It’s 6:30 AM on a weekday in the year 2030. You don’t wake up to a shrill phone alarm – in fact, your phone stayed on your desk last night. Instead, a gentle voice from an AI assistant woven into your bedroom softly nudges you awake: “Good morning. I’ve started the coffee. You have a meeting at 9, but the weather report suggests leaving 10 minutes early due to rain.” As you rub your eyes, a lightweight pair of smart glasses on your nightstand springs to life, projecting the morning’s headlines in the corner of your vision alongside your schedule. You slip them on; they look just like normal glasses, but with a subtle tint. You ask, “Any messages from overnight?” and a summary of texts and emails (curated by priority via AI) scrolls into view. No need to tap a screen – a slight flick of your gaze selects an email, and you dictate a quick reply, which the glasses’ AI assistant transcribes and sends.

During breakfast, you’re not hunched over a phone doom-scrolling. Your kitchen’s ambient AI reads you highlights of news you care about, and the smart display on the fridge shows a rotating gallery of photos your family shared recently. As you head out, you grab your AI wearable – it’s a sleek pendant that clips onto your jacket. This is the evolved form of the AI Pin: it houses microphones, a tiny speaker, and an array of sensors. It’s your ever-present companion, ready for voice queries or even silent ones (in 2030, it can detect subtle lip movements or neural signals for silent commands – a feature just rolling out, perhaps). On the commute, your car’s AI co-pilot takes over navigation. When a warning light blinks on the dash, you simply ask, “Car, what’s that about?” and the voice explains in plain language, even scheduling a service appointment proactively. Traffic is heavy, so you decide to get some work done: you dictate a document idea, and your wearable’s AI (connected to cloud) drafts a full memo for you by arrival, taking into account your past writing style and pulling in reference data as needed.

During the workday, the smart glasses assist you in subtle ways. In a meeting, they discreetly display names and roles next to unfamiliar faces – your personal CRM, ensuring you never forget a name. They live-translate a Japanese client’s speech in real-time captions, since you don’t speak Japanese fluently. When you tour a project site, the glasses overlay construction plans onto the actual structure, highlighting where an AI identifies a potential design issue. All of this happens without you whipping out a phone or laptop; computing has drifted into the context of whatever you’re doing.

After work, you stop by a grocery store. Instead of a shopping list on your phone, your glasses and wearable AI work in tandem: as you walk through the store, the glasses quietly highlight the items you need (having synced with your pantry inventory at home and recipes you’ve planned). Unsure about a product, you whisper “Hey, is this eco-friendly?” and your wearable’s speaker answers, citing the product’s sustainability rating from the web. Other shoppers don’t even notice you’re consulting an AI – there’s no device in hand, just you and a soft voice that might be mistaken for a phone call.

In the evening, you settle in for some entertainment. The living room’s immersive projection system (a successor to the TV) ties into your home AI; you say “Play the next episode of my show,” and it obliges, dimming the lights automatically. Your kids are doing homework – one of them asks their AI tutor (built into an AR desk lamp) a question about history, and it responds with an engaging, customized explanation.

Before bed, you realize you barely touched a traditional computer today. You did dozens of “computing” tasks – communication, writing, getting information, controlling appliances – but never once did you unlock a smartphone or sit down at a PC. The interfaces have melted into your life: voice when it’s convenient, glasses overlay when visuals help, ambient actions when AI can just handle it. Privacy is managed by transparent policies and personal AI settings – your devices politely chime or light up when recording, and most data processing happens locally or in encrypted form, so you feel secure. It’s a far cry from 2023, when so much of life revolved around staring at a 6-inch phone screen. The smartphone isn’t gone – it’s on your desk if you need a conventional touchscreen or a specialty app. But it’s no longer the center of attention. It’s more like a server in the background, while the “clients” – your glasses, wearables, home, and car – do the interacting.

In this imagined 2030, the post-smartphone era means personal computing is everywhere and nowhere. It’s personal not because you hold it in your hand, but because it’s woven throughout your personal space and context. OpenAI and Jony Ive’s bet is essentially on this vision – that the next chapter of technology will feel more natural, more human-centric, and be driven by AI at the core. We’re at the dawn of that era now. If the past was about converging everything into one device, the future is about the intelligence in that device breaking out and diffusing into all devices. It’s an exciting, daunting, and ultimately transformative shift – one that is just beginning, but promises to redefine how we live, work, and relate to technology by the time we ring in 2030.